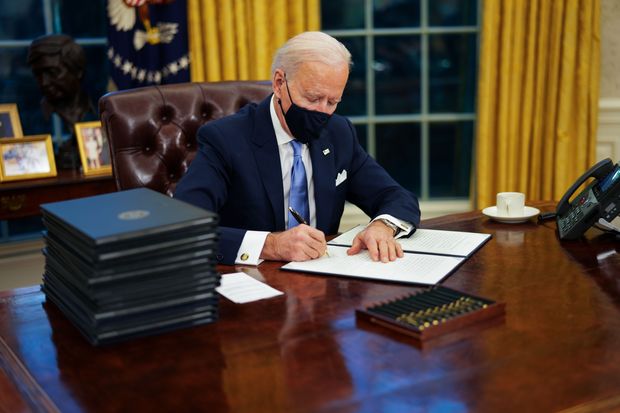

With the inauguration of President Biden and Vice President Harris behind us, it is important to reflect on what the new administration might mean for achieving racial equity in early care and education and how we can help. The next four years hold great potential, as evidenced by one of President Biden’s first acts: the signing of an Executive Order to advance racial equity and support communities that have been “systematically denied a full opportunity to participate in aspects of economic, social, and civic life.”

As Dr. Ibram X. Kendi writes in How To Be An Antiracist, “There is no such thing as a nonracist or race-neutral policy. Every policy in every institution in every community in every nation is producing or sustaining either racial inequity or equity between racial groups.” The Executive Order calls on federal agencies, including those that administer the nation’s early care and education programs, to use this critical lens to examine policies, programs, and services. Federal agencies must engage in specific actions that are designed to embed equity principles, policies, and approaches across the federal government. They will be required to:

- Identify methods to assess equity

- Conduct equity assessments for selected programs in federal agencies

- Allocate federal resources to advance fairness and opportunity

- Promote equitable delivery of government benefits and opportunities

- Engage with members of underserved communities and those experiencing discrimination

- Establish an equitable data working group

In a field where we are acutely aware of disparities in access to quality programs for families of color, it will be critical that we use this unprecedented opportunity to document and address the policies that perpetuate inequity. This Executive Order also provides opportunity to significantly address the long-standing problems around disparate pay and leadership opportunities afforded to Black and Brown early childhood professionals and women of color.

Using the Executive Order to support racial equity in early care and education

The Order applies across the entire federal government and its policies and programs—ranging from criminal justice to commerce—and agency secretaries have plenty on their plates rebuilding their agencies while addressing the pandemic. It will be important not to let this Executive Order be washed away in the tidal wave of work facing the administration, so it is up to us to ensure that its goals are realized for early care and education.

Here are three things that must happen to make sure the Executive Order has an impact on our field:

- Ensure that the early care and education programs administered by the U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services, Education, and Agriculture are part of the equity assessment.

The Executive Order allows the head of each agency to “select certain of the agency’s program and policies for review.” This flexibility means that early care and education programs could be excluded from the Order, resulting in no benefit to our community or the children and families we serve. Accordingly, it will be important that Secretaries Becerra, Cardona, and Vilsack have letters from us waiting for them when they are confirmed that outline our numerous racial equity concerns that are either perpetuated by or could be solved with changes to federal early childhood programs. At a minimum, the programs that must be a part of the review include:

- Head Start,

- The Child Care and Development Block Grant,

- The Preschool Development Grant Birth-5,

- IDEA Part C and Part B (Section 619),

- The Child and Adult Care Food Program, and

- The Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program.

Our letters must clearly identify the programs and services we want included and why they need to be evaluated in an equity assessment.

- Dig deep into the anatomy of early care and education policies to uncover elements of structural racism.

Once it is ensured that early care and education policies will be addressed as part of the Executive Order, it will be important that early childhood stakeholders become involved in developing the framework for the assessment. A framework for any equity assessment of early childhood programs must include, at minimum, a review of the following policy characteristics:

- Eligibility criteria. Determining who is eligible for early childhood programs and services is a necessary (but not sufficient) component of equitable access. These eligibility criteria vary widely across programs and are significant factors in the disparities in access to high-quality early care and education programs.

- Funding levels. Inadequate funding deprives some eligible children and families of access to programs and services. A lack of funding also disproportionally impacts the quality of programs and services for children and families of color, the compensation of providers of color, and the physical environments in which children of color are placed.

- Administrative processes. Agency effectiveness in implementing policies is as important as the policies themselves to ensuring equitable access and benefits. Issues with program administration begin with the lack of diverse leadership in positions of power and pervade every aspect of implementation down to the complexity of the application for services.

- Program standards. Program standards define the experiences of children in early childhood programs and play a significant role in either promoting or undermining the equitable treatment and opportunities of children of color. The extent to which these standards reflect and support the values of culturally diverse families and educators and serve to promote children’s developmental, nutritional, and educational needs are fundamental aspects of equity, which the assessment must address.

- Workforce supports. The ECE workforce is highly stratified by race in terms of leadership roles, responsibilities, and compensation. Attention must be paid to the policies that contribute to these power imbalances (e.g., education requirements, career ladders, funding of leadership programs).

- Early learning standards, assessment, and accountability. The way in which early care and education programs and services define success and how they are assessed against this definition have significant implications for racial equity. Any equity assessment must determine the impact of how the field measures program quality, classroom quality, and school readiness for children and providers of color.

It is through an assessment of these structural features of early care and education policy that we can derive actionable recommendations and strategies that promote access, quality, and benefits for children and families of color and other groups that have been underserved by early care and education programs. This framework will also provide a template for states and localities to engage in their own equity assessments.

- Be aware that both competition and flexibility can exacerbate racial inequity.

There are two other critical aspects of how early care and education funding is allocated that need to be examined from a racial equity perspective. First is the allocation of funding through competition. Typically, policymakers and administrators view competition as a sound way of being good stewards of federal and state funding. The competitive process typically involves applications that require the creation of a plan and budget, and a discussion of a state’s or organization’s capacity to implement the funding. Historically, however, the competitive process has undermined the ability of the lowest-capacity states and organizations—those most in need—to be successful in drawing down this funding. For example, the poorest states in the country, including Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, South Carolina, and others, never received Race to the Top Early Learning Challenge funding—an early signature initiative of the Obama Administration—even after three rounds of competition. At the very least, competitive processes must be altered to place significant weight on serving underserved populations and must support applicants with technical assistance to increase the capacity of under-resourced states and organizations to compete for grants.

A second aspect, flexibility in the use of funding, also needs to be examined from a racial equity perspective. Allowing the traditional power structures to determine how federal funding is allocated at the state and local levels only works to maintain the status quo. While policymakers argue that officials request flexibility to meet the unique needs of their state or locality, this discretionary funding becomes the target of lobbying and advocacy campaigns that are won by those with the most political power and resources. Accordingly, a serious look must be taken at how to provide flexibility that helps states and localities drive toward, instead of undermining, racial equity.

This Executive Order is an historic opportunity for the field of early childhood, a space plagued by fragmentation, inequitable distribution of resources, and barriers to access that unfortunately dictate the realities of millions of children’s experiences during their most critical years of development. Until we can ensure that all children and all caregivers in all settings have equitable access to the supports and resources they need to thrive, we will continue to fall short of the great promise of our field.

This Executive Order is a first step. We need to come together as a field to see the work through.

Stay tuned to the Equity Insider—there is more to come.

Sincerely,

The Policy Equity Group Team