Although many people don’t think of babies or preschoolers as having mental health, every April 23rd is World Infant, Child, and Adolescent Mental Health Day. The inclusion of our youngest children is a reminder that children’s emotional experiences are no less valid than adults’ and that early experiences are the building blocks for lifelong wellness. This day of recognition is also an opportunity to reflect on the history and future of the field of infant and early childhood mental health (IECMH).

What is Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health?

In the 1970’s, social worker Selma Fraiberg and her colleagues pioneered an approach that focused on understanding and supporting children’s well-being within the context of their caregiving relationships. They called this approach “Infant Mental Health”. It has since expanded to include children birth through age 5 and spans the disciplines of mental health, early childhood, special education, medicine, and social work.

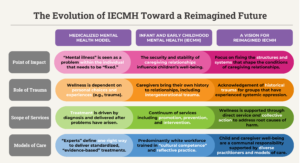

The Evolution of IECMH

The field of IECMH has been instrumental in pushing people’s understanding from “What’s wrong with that child?” to “How are this child’s relationships and environments contributing to their behavior and self-concept?” The emphasis on caregiving relationships and increased sensitivity to the effects of trauma, toxic stress, and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have been a critical point of evolution in supporting children’s mental health. However, it is time to advance the field again. The table below shows how IECMH has diverged from the “disease model” of mental health and charts a course toward a reimagined future.

Moving Upstream

In a classic parable, a child is seen drowning in a river, followed by another child, and then another. While rescuers work frantically to save the growing number of children, a wise person walks upstream to investigate why children are falling in the river. Like the rescuers in the story, the IECMH field has worked doggedly to help families stay afloat amidst the currents of trauma and equip children with lifejackets of social–emotional skills.

While trauma-informed care and teaching social–emotional coping techniques are essential, alone they are insufficient. As activist and education expert Dena Simmons notes, “Try telling a child in poverty to breathe through racism. That is insulting.” Transforming the conditions of children’s mental health requires downstream work and repair of the broken bridges upstream. Otherwise, this unending flow of children experiencing trauma and harm will never stop.

Broken Bridges

Disruptions to caregiving relationships can have significant implications for children’s mental health. Despite this, patterns of unjust separations and loss are perpetuated each time:

- A child loses a caregiver to police violence or incarceration at the hands of our inequitable and biased criminal legal system;

- A child welfare agency removes a child from their home for conditions that reflect poverty or cultural differences rather than parental incompetence;

- A new parent is forced to return to work within weeks of a child’s birth, missing critical bonding time with their newborn because paid leave is unavailable; or

- A child experiences multiple losses in relationships with child care providers because poverty-level wages lead to massive turnover within the field.

Providing IECMH services for children navigating caregiver separation and loss is essential, but we cannot let the need for these downstream supports obscure the fact that these unjust separations should not happen in the first place. Nor can we ignore our country’s violent history of separating families of color through the trade of enslaved people, the forced removal and assimilation of Native children in boarding schools, and inhumane immigration and asylum policies. For too long, children’s mental health has been the collateral damage of institutions, policies, and systems that sanction and perpetuate conditions of trauma, toxic stress, and ACEs.

Children’s Mental Health and Collective Liberation

To effect meaningful and lasting change, the field of IECMH will need to shift from a mindset of healing the effects of individual trauma to also combatting the collective trauma of oppression. This “both/and” approach requires:

A New Frame. Yes, IECMH work can change individual trajectories of brain development, learning potential, social–emotional well-being, and long-term health. But this work is also essential to transforming our collective future given the increasingly complex problems we face. Our future citizens, leaders, and changemakers will need:

- Strong social skills to constructively negotiate conflict and problem-solve across growing social and political divides;

- Self-regulation skills to choose the long-term health of our planet over what is fast, easy, or convenient; and

- Emotional literacy and empathy to form strong communities rooted in justice and mutual aid.

A New Invitation. Beyond framing children’s mental health as a universal priority, the landscape of IECMH needs to change. We need to call in new “non-traditional” partners and help them see the relevance of IECMH to their work and what they can do to rebuild the bridges upstream. We need employers and policymakers to see that a well-resourced child care system is crucial for child development and economic development. We need to address structural racism in higher education to create equitable opportunities for everyone’s economic mobility and ensure a more diverse workforce of IECMH professionals to better serve all children and families.

A New Call to Action. As we bring others into the IECMH fold, the infant and early childhood mental health community can also engage in and amplify work in other sectors advocating for transformative change. We invite you to explore this list of 10 actions you can take to fight for IECMH:

Preventing caregiver loss and separation

-

- Advocate for reducing caregiver incarceration and support abolitionist movements.

- Learn about dismantling the child welfare system to support and strengthen rather than surveil and separate families.

- Support organizations and amplify the voices of those fighting for paid family leave.

- Connect with movements that uplift early childhood professionals and other key care providers to decrease turnover in caregiving.

Minimizing stress for children and caregivers by meeting essential needs

-

- Explore what safe, stable, affordable housing for all families and educators actually looks like.

- Support access to affordable, culturally relevant, nutrient-dense foods.

- Advocate for equitable access to healthcare—including mental health supports—as well as redesigning systems of healthcare and healing outside the current medical industrial complex.

Averting future traumatic experiences

-

- Help avoid future trauma, relocation, and loss for families due to (un)natural disasters by fighting for climate solutions.

- Support more direct and proactive investment in communities to prevent community and police violence.

- Join the fight for common-sense public safety measures and policies that can protect everyone from gun violence.

If we begin to look closely, work that advances our collective liberation—racial, economic, gender, disability, and environmental justice—also underwrites children’s mental health. As abolition organizer, educator, and activist Mariame Kaba says, “Changing everything might sound daunting, but it also means there are many places to start, infinite opportunities to collaborate, and endless imaginative interventions and experiments to create.” We lean into these infinite opportunities to invent a new world where all work is children’s mental health work and children’s mental health is everyone’s work.

—

Acknowledgments

Our understanding of how our work in early childhood is both complicit in and intersects with multiple structures of oppression is constantly evolving and being challenged. We are inspired and grateful for the work and wisdom of many individuals and organizations such as Nicole Cardoza and the Anti-Racism Daily staff, Dr. Jennifer Mullan of Decolonizing Therapy, Britt Hawthorne, Dorothy Roberts, Mariame Kaba, Dena Simmons, Ed.D., and Heather McGhee. This piece was also informed by discussions with the Maryland IECMH Framework Workgroup.

Photo credit: Pixabay